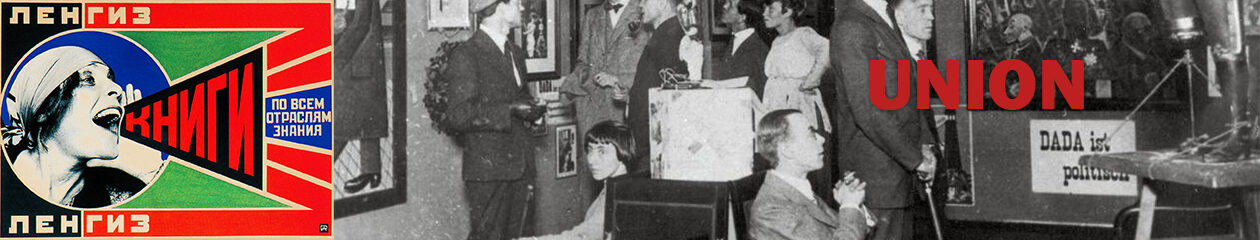

Dada (/’da:da:/) or Dadaism was an anti-establishment art movement that developed in 1915 in the context of the Great War and the earlier anti-art movement.

Hugo Ball, 22 February 1886 – 14 September 1927) was a German author, poet, and essentially the founder of the Dada movement in European art in Zurich in 1916. Among other accomplishments, he was a pioneer in the development of sound poetry.

Dada emerged from a period of artistic and literary movements like Futurism, Cubism and Expressionism; centered mainly in Italy, France and Germany respectively, in those years. However, unlike the earlier movements Dada was able to establish a broad base of support, giving rise to a movement that was international in scope. Its adherents were based in cities all over the world including New York, Zürich, Berlin, Paris and others. There were regional differences like an emphasis on literature in Zürich and political protest in Berlin

Prominent Dadaists published manifestos, but the movement was loosely organized and there was no central hierarchy. On 14 July 1916, Ball originated the seminal Dada Manifesto . Tzara wrote a second Dada manifesto, considered important Dada reading, which was published in 1918. Tzara’s manifesto articulated the concept of “Dadaist disgust”—the contradiction implicit in avant-garde works between the criticism and affirmation of modernist reality. In the Dadaist perspective modern art and culture are considered a type of fetishzation where the objects of consumption (including organized systems of thought like philosophy and morality) are chosen, much like a preference for cake or cherries, to fill a void.

The shock and scandal the movement inflamed was deliberate; Dadaist magazines were banned and their exhibits closed. Some of the artists even faced imprisonment. These provocations were part of the entertainment but, over time, audiences’ expectations eventually outpaced the movement’s capacity to deliver. As the artists’ well-known “sarcastic laugh” started to come from the audience, the provocations of Dadaists began to lose their impact. Dada was an active movement during years of political turmoil from 1916 when European countries were actively engaged in World War I, the conclusion of which, in 1918, set the stage for a new political order.

Wikipedia Contributors (2025). Dada. Wikipedia

Subversive and irrelevant, Dada, more than any other movement, has shaken society’s notions of art and culture production. Fiercely anti-authoritarian and anti-hierarchical, Dada questioned the myth of originality, of the artist as a genius, suggesting instead that everyone should be an artist and that almost anything could be art. Surrealism, constructivism, Lettrism, situationism, Fluxus, pop and Op Ar, conceptual Art and Minimalism: Most twentieth-century Art movements after 1923 have traced their roots to Data. Dada works still have as radicality and freshness that attracts today’s culture jammers and disrupters of life as usual.

Dietmar Elger and Uta Grosenick (2016). Dadaism. Koln, Germany Taschen.

Kuenzli, R.E. (2015). Dada. London: Phaidon.

Hannah Hoch:

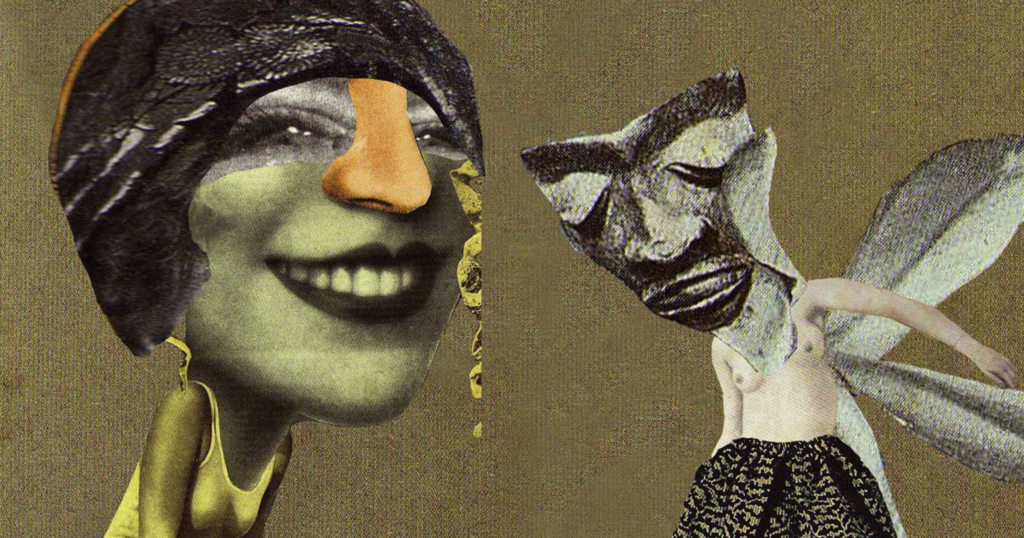

Hannah Höch: 1 November 1889 – 31 May 1978) was a German Dada artist. She is best known for her work of the Weimar period, when she was one of the originators of photomontage. Photomontage, or fotomontage, is a type of collage in which the pasted items are actual photographs, or photographic reproductions pulled from the press and other widely produced media.

An important element in Höch’s work was the intention to dismantle the fable and dichotomy that existed in the concept of the “New women”: an energetic, professional, and androgynous woman, who is ready to take her place as man’s equal. Her interest in the topic was in how the dichotomy was structured, as well as in who structures social roles.

Other key themes in Höch’s works were androgyny, political discourse, and shifting gender roles. These themes all interacted to create a feminist discourse surrounding Höch’s works, which encouraged the liberation and agency of women during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and continuing through to today.

Wikipedia Contributors (2019). Hannah Höch. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_H%C3%B6ch

In 1912, Hannah Höch began to study at the Kunst-gewerbeschule in Berlin. Later she transferred to the Staatliche Lehranstalt des Kunstgewerbemuseums. In 1915, during this period, she met Raoul Hausmann. Both were at that time associated with the circle centring on Herwarth Walden’s gallery Der Sturm. Through, Hausmann, she subsequently made the acquaintance of the Berlin Dadaists. Johannes Baa-der gave her the title “Dadasophess”, a friendly allusion to her lover, the “Dadasopher” Raoul Hausmann. The “h” at the end of her first name was added by Kurt Schwitters in 1921, on the grounds that it made her name palindromic, like the Anna in his Merz poem “An Anna Blume’.

Hannah Höch was a collector. In her hidden-away summerhouse in her garden in the Heiligensee district of Berlin, she assembled numerous documents, materials, and records of Dadaism, arranged them according to a system comprehensible only to her, and thus preserved many ephemeral witnesses to the movement over the decades. After her death in 1978, the Berlinische Galerie acquired the archive and arranged it on more scholarly principles. This 1922 collage My Domestic Mottoes (Meine Haus-sprüche) is also a collection of Dadaist souvenirs. The Dadasophess Hannah Höch was never a theoretician. She preferred to leave definitions of position to others, first and foremost her lover Raoul Hausmann. The collage also has room, however, for many other of her friends and fellow-Dadaists. My Domestic Mottoes is Hannah Höch’s little ironic self-portrait as reflected in quotations from Kurt Schwitters, Hans Arp and Johannes Baader. The collage comes across as a sort of pin-board, on which the background is formed by various papers with decorative patterns, photographic depictions, scientific illustrations and a detail of a map. The mechanical motif of the ball-race appears here too. And once again she has not so much composed her materials as simply added them one after the other. As already in the Incision with the Dada Kitchen Knife through Germany’s Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch, the beholder can find her self-portrait here too, hidden between the other elements of the collage. On top of the papers stuck to the cardboard, Hannah Höch has written some pithy Dadaist slogans and signed them with the names of their authors. “Only an undecided mixture is dangerous” derives from Raoul Hausmann; “Let them say they don’t know where the church tower stands” is a quotation from Kurt Schwitters’ poem “An Anna Blume”. And the insight “Dada polices the police” is due to Richard Huelsenbeck. It is through these slogans, carefully written out in neat handwriting, that the work gets its vitality. By 1922 the Berlin Dadaist movement had already broken up. Its individual members had begun to go their own ways or to forge new coalitions. One such project in September of that year was the “International Congress for Constructivists and Dadaists”, held at the Bauhaus in Weimar. Hannah Höch’s personal relationship with Raoul Hausmann also broke up. In her Domestic Mottoes she had united all the Dadaists once more: Hans Arp from Zurich, the Hanover Merz artist Kurt Schwitters, and the Berliners Richard Huelsenbeck, Walter Serner and Raoul Hausmann. She herself is looking somewhat shyly from behind a pale grid. The collage preserves those Dadaist mottoes which were to accompany her artistic work in the subsequent decades of her life. Even though in the future Hannah Höch was to devote much more of her time to painting once more, the principle of photomontage and collage continued to characterize her artistic output.

Kuenzli, R.E. (2015). Dada. London: Phaidon

“I wish to blur the firm boundaries which we self-certain people tend to delineate around all we can achieve.”

Photo Analysis:

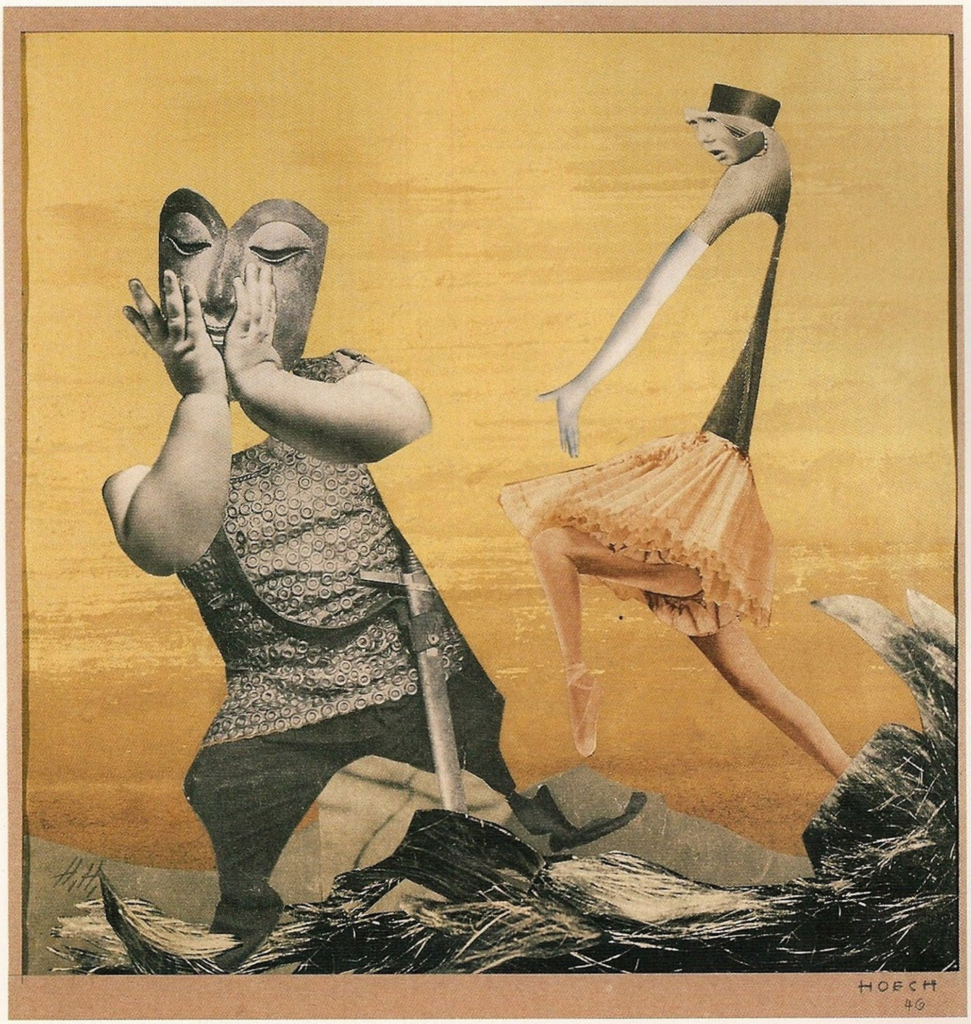

Although this isn’t a photograph, and it is a montage, it helps to see what artists back in the day used to do with their art. I really like how they place some random objects together, the aim of Dada is to challenge the social norms of society, and purposefully make art that would shock, confuse, or outrage people. It’s seen as a different style of art. Dada was an art movement formed during the First World War in Zurich in negative reaction to the horrors and folly of the war. The art, poetry and performance produced by Dada artists is often satirical and nonsensical in nature. I really like how the background of the photo is bright and elevating, it adds a contrast to the rest of the objects in the surroundings. This montage is clearly showing the power of different objects put together and it shows a sense of make believe things put together. The whole aim of Dadism is to capture the horrors and the truth of the second world war and this photo is doing exactly that. The people seems to be wearing some sort of armour, something a soldier would wear in the war. Though there is also another person who seems to be wearing some sort of dress, there body has been messed around with and slimmed down. Almost as if different peoples bodies have been put together, at the bottom of the image there is grass that has been put in black and white. Most of the objects added to this montage are quite colourless and faded away and the bright background helps to bring everything else back to life. The first person on the left is clearly wearing an armour suit with a sword but has miss proportioned legs and feet compared to the rest of the body. The use of the arms adds emotions, some sort of worry or caution to the surroundings, while the face is a mask, the person is hiding their identity or possibly hiding from the world of war, they are trying to escape the reality whereas the person on the right is clearly some kind of dancer or ballerina, the use of the big puffy skirt, with the slim waist and the expression on the face, all together both people have different types of purposes on this page, just like they did back in the past, men during the war had to fight and not show any of their fears, they had to put on a mask and fight for their country whereas stereotypically women stayed at home and did the cooking, they didn’t have to get their hands dirty. This could be the representation that the artists is trying to put out. Though I’m not too sure what the grass could represent between the two people. For the person on the left the grass could be a symbol of a familiar surrounding, as the war is mainly outside on a battle field surrounded by the grass, but for the other person on the right I’m not too sure what the grass could represent, it could be a symbol of the happiness before or after the war, the idea that war is finished and the grass is slowly becoming healthy again or that before the war the grass was an important factor to that specific country, it could also just be the ground so that the people aren’t floating. Overall I would say that this photo has an interesting representation of the war and uses quite dull colours to represent the dark time and the background being bright makes everything else stand out and look more visible.

What is Dadaism? Some explanations and definitions. (n.d.). Available at: https://learn.ncartmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/What-is-Dadaism_0.pdf

Chanelle, to have an overview of how your exam project is developing, it would be good if you published:

1. Statement of Intent

2. Artists Case studies x 2

3. New photoshoots in response to the above